Inguinal Hernia: A Probable Complication of Urinary Schistosomiasis in School Age Male Children in an Area Highly Endemic for Schistosoma Haematobium in Zambia.

Abstract

Introduction

Schistosoma haematobium infection is acquired early in life with the peak prevalence and intensity of infection occurring in the second decade of life in endemic areas. The aim of this study was to establish any association between S. haematobium infection and development of inguinal hernia in school age children in a S. haematobium highly endemic area in Zambia.

Methodology

An analytical study was conducted at St Paul’s Mission Hospital, Nchelenge, Luapula province, Zambia. Hospital operating theatre records were reviewed for inguinal hernia repair operations in school age children.

Results

There were 45 inguinal hernia repair operations conducted in male school age children presumed to be infected with S. haematobium between July 2010 and July 2015. The mean age of these children was 9.6 years while the age range was from 6 years to 14 years. The overall prevalence of S. haematobium in school age children in the area ranged from 89.5% to 95.5% during this period.

Conclusion

Inguinal hernia is a probable complication of S. haematobium infection in school age male children.

Author Contributions

Academic Editor: Prachi Arora, University Of Wisconsin - Madison

Checked for plagiarism: Yes

Review by: Single-blind

Copyright © 2017 Victor Mwanakasale, et al.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Competing interests

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Citation:

Introduction

Urinary schistosomiasis is caused by the schistosome Schistosoma haematobium. Over 112 million people in sub-Saharan Africa alone are infected by S. haematobium annually1. The infection is acquired quite early in life with both the prevalence and intensity of infection peaking in the second decade of life2. Hence school age children are prone to this infection in endemic areas. The infection is asymptomatic in most cases. Symptomatic cases may present with haematuria which is terminal, abdominal pains, dysuria affecting about 30 million people in endemic areas1, and straining on urination3. Complications of schistosomiasis haematobium reported in literature include cystitis and ureteritis which may progress to squamous cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder, hydronephrosis and hydroureters affecting 10 million people in endemic area of the world, renal failure leading to 150,000 deaths annually1, and Central Nervous lesions such as transverse myelitis with flaccid paraplegia4. No other complications of schistosomiasis haematobium requiring surgical intervention have been reported in literature.

During a study in which we screened school children aged between 5 and 14 years for S. haematobium at Kenani and Chandwe Primary schools in Nchelenge, Luapula province of Zambia in 2005 we found the prevalence of S. haematobium to be 95.5% and 89.4 %, respectively5. This literally meant that all the school age children in this region were infected with S.haematobium. We observed that some of the school children in the study had difficulties in submitting the required volume of urine for the urine filtration and examination for S. haematobium ova procedure. The volume submitted by these children was too little. We made an assumption that due to the infection, the affected children were straining themselves to urinate and give the required volume of urine. Straining on urination has the risk of raising the abdominal pressure with a probability of the affected individual developing inguinal hernia6.

In this article we present findings from a review of the operating theatre records on inguinal hernia repairs conducted on school age children admitted to St. Paul’s Mission Hospital in Nchelenge district of Zambia between July 2010 and July 2015. The aim of this study was to establish any association between S. haematobium infection and occurrence of inguinal hernia in school age children in an area highly endemic for S. haematobium.

Methodology

Study Design

This was an analytical study. Hospital operating theatre records for school age children admitted were reviewed for a specific period.

Study Site

The study site was St Paul’s Mission Hospital in Nchelenge district (coordinates: E-28 43.920, S-9 20.729). The hospital has a capacity of 250 beds. The prevalence of S. haematobium infection in school age children in the study area remained the same since 2005 as no intervention was instituted by the government of Zambia since that time to control schistosomiasis in this district.

Study Population

Only operating theatre records for school age children were reviewed.

Data Collection

Permission to review the operating theatre records at St Paul’s Mission Hospital was obtained from the Hospital administration. The review of the records was conducted by one of the co-authors in July-August 2015.The period of the review was from July 2010 to July 2015. The following parameters were recorded; age, sex, date of the inguinal hernia repair, and type of hernia repair procedure in school age children admitted at the hospital. No variables that could link a patient to the information obtained such as the name and patient file number were collected from each patient’s file.

Data Management

Data was entered and analysed in Epinfo 6.04c

Results

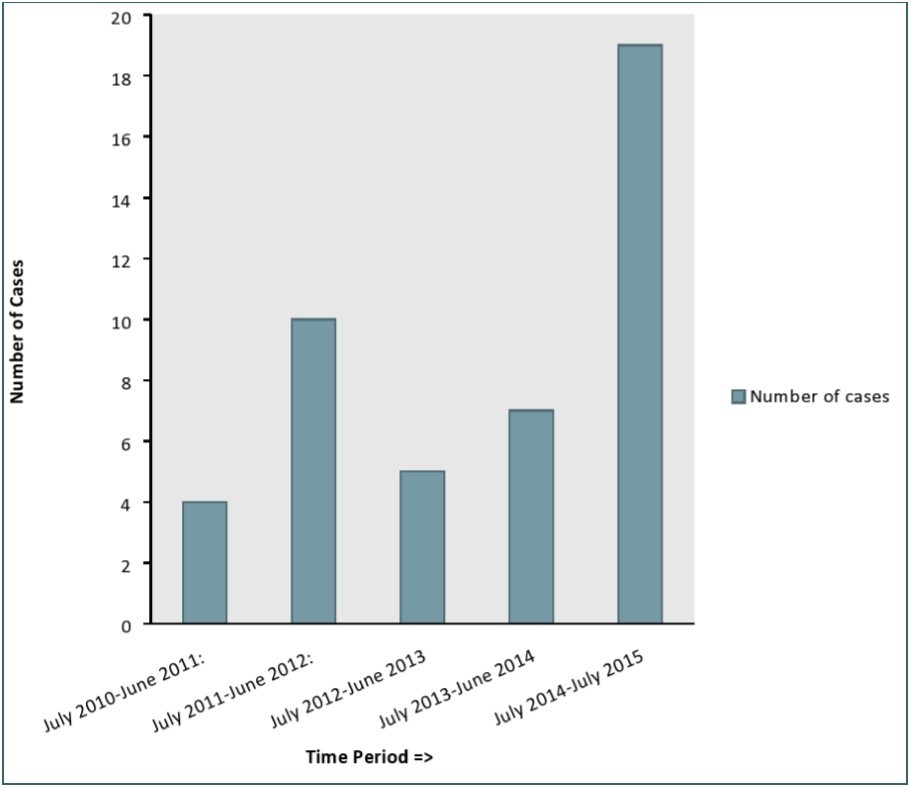

Review of the hospital operating theatre records showed that a total of 45 hernia repair operations for inguinal hernia were conducted on school age children from July 2010 to July 2015. Modified Basini technique7 was used in the repair of the hernias in all the cases. This was because the hospital lacked mesh. The age distribution of the children is shown in the Table 1 below. The mean age of the children was 9.6 years (SD=2.6 years). The minimum age of these children was 6 years while the maximum age was 14 years. The most affected age was 8 years. All the children were boys. The distribution of inguinal hernia cases in the school age children over the period from July 2010 to July 2015 is shown in the Figure 1 below. Most cases of inguinal hernia were operated on between July 2014 and July 2015. The threatre records didn’t have information on the size of the hernias operated. In addition no ultrasound studies were conducted on the children prior to the operation.

Table 1. Age distribution of inguinal hernia cases in school age children| Age of child in years | Frequency |

|---|---|

| 6 | 5 |

| 7 | 7 |

| 8 | 10 |

| 9 | 2 |

| 10 | 1 |

| 11 | 6 |

| 12 | 7 |

| 13 | 3 |

| 14 | 4 |

| Total | 45 |

Figure 1.Distribution of inguinal hernia cases from July 2010 to July 2015.

Discussion

Given the high prevalence and intensity of infection and intense transmission of S. haematobium in this region of Zambia5, an assumption was made that all the 45 inguinal hernia cases in the school age children were infected with S. haematobium. Inguinal hernia in these children most likely developed as a result of straining during micturition which over time led to increased abdominal pressure3. Straining during micturition in schistosomiasis haematobium may be due to chronic retention of urine as a result of atonic urinary bladder. The atonic urinary bladders results from fibrosis of muscle layer of the urinary bladder which leads to urinary bladder contraction3. Another cause of chronic retention of urine in schistosomiasis haematobium is the urinary bladder neck obstruction as a result of intense fibrosis following S. haematobium oviposition at this site3.

Inguinal hernia occurs when the fascia transversalis fails to withstand the stresses of normal or increased intra-abdominal pressure6. The fascia transversalis is a thin layer of fascia lining the transverses abdominis and the extraperitoneal fascia. Raised intra-abdominal pressure may occur in situations such as straining during bowel movements as in chronic constipation or urination, lifting of heavy objects, ascites, pregnancy, excess weight, chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases, and others. Therefore straining during micturition is a plausible cause of inguinal hernia in school age children infected with S. haematobium.

To support our hypothesis that raised abdominal pressure led to the development of inguinal hernia we would in future studies use reliable methods to measure urinary flow such as the ultrasound (probe placed around the base of the penis) and the funnel with a rotating disk at the bottom8. To further test our hypothesis in future we would measure the “time to pee” of children with schistosomiasis, with schistosomiasis and hernia, and with no schistosomiasis but with hernia. In addition ultrasound studies would help in determining the extent of schistosomiasis pathology in the ureters and the bladder. To prove our hypothesis true that inguinal hernia is a complication of S. haematobium infection, rather than look at schistosomiasis prevalence in non-hernia children, we would have to compare the intensity of schistosomiasis (egg count in 10 mls of urine) between children with hernia and those children without hernia. If our hypothesis is true we would expect children with heavy infection to have hernia and while children with light infection to have no hernia. With the high prevalence of schistosomiasis in this region we wouldn’t get enough sample size of children without schistosomiasis and with or without hernia to make statistically significant interpretation.

Conclusion

Inguinal hernia is most likely a serious complication of schistosomiasis haematobium in school age children living in areas highly endemic for S. haematobium. If this hypothesis is proven correct effective schistosomiasis control programs would reduce the incidence of inguinal hernia in school age children in regions with high transmission of S. haematobium. This would improve the health status of school age children leading better performance in school for those that attend school. More studies are required to prove our hypothesis correct.

Funding

Funding for this research was provided by the National Institute of Parasitic Diseases, CDC-China, Shanghai, People’s Republic of China.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Dr Shadreck Chama, the Acting Vice Chancellor of the Copperbelt University, for having authorized the execution of this study in the university. We are also grateful to Professor Kasonde Bowa, the Dean of School of Medicine at the Copperbelt University, for having supported this study. We also thank the staff in the records room at St. Paul’s Mission Hospital for their cooperation.

References

- 1.Luke F, Pennington, Michael H Hsieh. (2014) Immune response to parasitic infections.elSBN: 978-1-60805-148-9.Bentham e books. 2, 93-124.

- 2.WHO. (1998) Guidelines for the evaluation of soil-transmitted helminthiasis and schistosomiasis at community level.WHO/CTD/SIP/98.1.

- 4.Freitas A R, Oliveira A C, Silva L J.Schistosomal myeloradiculopathy in a low-prevalence area: 27 cases (autochonous in Campinas. Sao Paulo,Brazil”.Mem.Inst. Oswaldo Cruz(July2010):. 105(4), 398-408.

- 5.Victor Mwanakasale.Siziya Seter, Mwansa James, Koukonari Artemis, Fenwick Alan. Impact of iron supplementation on schistosomiasis control in Zambian school children in a highly endemic area.Malawi Med J.2009,March:. 12-18.

- 6.Abrahamson Jack. (2001) Mechanism of Hernia formation. Abdominal wall Hernias: Principles and management.Springer Science Business , Media New York .