Immunotherapy Usage Has Not Increased Sub-Lobar Pulmonary Resections Despite Reduced Pneumonectomies

Abstract

Objective

The landscape of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) has changed due to liberalized utilization of computed tomography, developments in immunotherapy and targeted treatments, and guidelines encouraging sublobar resections. We analyzed the implications of these advances for surgical procedures over a 16-year period.

Methods

The National Cancer Database was used to identify NSCLC incident cases from 2004 to 2020. Histology, stage, grade, and treatment were analyzed using descriptive statistics and logistic regression.

Results

2,028,553NSCLC patients were identified. Each year was associated with an increase in Stage I for NSCLC (OR1.05, 95%CI 1.05-1.05) and histological subtypes (adenocarcinoma: OR1.03, 95%CI 1.03-1.04; squamous: OR1.02, 95%CI 1.02-1.02; neuroendocrine: OR1.11, 95%CI 1.11-1.12), with no change in adenosquamous histology. A similar increase was observed for well- or moderately-differentiated histology (OR1.04, 95%CI 1.04-1.04). The proportion of patients receiving chemotherapy decreased (OR0.98, 95%CI 0.98-0.98), while more patients were treated with immunotherapy or targeted therapy, including an increase of 14% using immunotherapy or targeted therapy as first-line treatment.

There was a decrease in the likelihood of receiving pneumonectomy (OR 0.91, 95%CI 0.91-0.91). Despite guidelines advocating sublobar resections, these procedures only increased by 1.1% per year.

Conclusions

Over the 16-year study period, there was a significant trend towards diagnosis of Stage I NSCLC. The most pronounced change in treatment patterns has been more patients receiving immunotherapy and less chemotherapy. Despite a promising decrease in pneumonectomies, the frequency of sublobar resections remains stagnant, indicating limited uptage in current practice.

Author Contributions

Academic Editor: Talha Bin Emran, BGC Trust University Bangladesh

Checked for plagiarism: Yes

Review by: Single-blind

Copyright © 2026 Kelly A. McGovern, et al.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Citation:

Introduction

In 2024, lung cancer caused 234,580 new cases and 125,070 deaths in the US, making lung cancer the most common cause of cancer death.1 In recent decades, diagnostic and therapeutic advancements have enhanced our ability to diagnose and treat lung cancer and have dramatically altered lung cancer management, including immunotherapy, screening, and improvements in lung preservation.

One of the most significant changes in treatment of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is the addition of targeted therapies and immunotherapies in combination with chemotherapy for patients with actionable oncogenic alterations.2, 3 Since the discovery of immunotherapy, the therapeutic options for patients with advanced-stage NSCLC have dramatically expanded, and the treatment paradigm is still evolving.4, 5

The landscape of NSCLC care has also changed with surveillance. Annual low-dose computed tomography is now recommended under many organization guidelines and has resulted in more widespread NSCLC screening.6

Based on recent studies including CALBG140503 and JCOG0802, showing non-inferiority of sublobar resections compared to lobectomy, there has been a shift in thoracic oncology towards sublobar resections for small, early-stage lesions.7, 8, 9, 10 A sublobar resection allows for preservation of lung function while still obtaining full oncologic resection. Despite these recommendations, widespread adoption of this practice remains unknown.

The National Cancer Database (NCDB) is the largest cancer registry in the world, reporting data from 70% of newly-diagnosed cancer cases nationwide.11 Given the changing landscape of NSCLC, we aimed to harness the vast information in the NCDB to analyze the diagnostic and therapeutic trends of NSCLC in the US, specifically how use of immunotherapy and surgical treatments changed over time, and to see how trends were impacted by histology.

Methods

Patient Selection

The NCDB Public Benchmark Report was queried for patients with NSCLC between 2004 and 2020. Patients included are described in Supplemental Table 1. Exclusion criteria included histology suggestive of small cell carcinoma or non-NSCLC pulmonary metastases, and diagnosis after 2020. Data did not include individual or identifying information and the study was approved by the NCDB. This study was approved by the university Institutional Review Board.

Definition of Variables

Patient and tumor information including age at diagnosis, histology, stage, grade, treatment, and months elapsed from diagnosis to date of death/last contact were extracted. Histology was stratified into adenocarcinoma, adenosquamous, neuroendocrine, and other histologies.

Staging in the NCDB was assigned according to the 7th edition of the American Joint Commission on Cancer (AJCC), acknowledging the change from AJCC 7th edition to 8th edition in 2018. Stage was assigned the value of the pathologic stage, or clinical stage if pathologic stage was unavailable. Stage values used were from time of diagnosis, excluding patients with occult or stage 0 disease.

Grade was assigned according to the 7th edition of the AJCC, acknowledging the change to the 8th edition staging system in 2018. Grade was defined according to pathologic diagnosis of cancer resemblance to normal tissue. If multiple grades were assigned, the highest grade was used.

Surgery performed was categorized into: wedge resection, segmental resection, lobectomy/bilobectomy, and pneumonectomy. Surgery included only definitive surgery to the primary tumor.

The use of systemic chemotherapy was assessed for use as first-line treatment. Patients were grouped by whether they received systemic chemotherapy or not. Immunotherapy and targeted therapy, described by the NCDB and henceforth as “immunotherapy”, was assessed for use as first-line treatment. Patients were grouped by whether immunotherapy or targeted therapy was administered or not, beginning in 2011 when immunotherapy was FDA-approved.

Overall survival (OS) was assessed using months elapsed from the date of diagnosis to the date of last contact or death, whichever occurred first. Patients diagnosed after 2017 were excluded from analysis to ensure 5-years of follow-up between diagnosis and date of reporting (2023).

Analysis

Analyses were performed using R software (version 4.4.0). Patients were analyzed in cohorts (Supp.Table 1), excluding patients with missing/unknown data. Descriptive statistics are represented in percentages. Changes in proportions are reported as percentage-point changes. Logistic regression was used to estimate change in percentages by year. A sensitivity analysis fit separate logistic regressions for Stage I diagnosis and grade before and after January 1, 2018 to account for the change in AJCC guidelines. A linear spline regression with one knot at 2014 was used to analyze immunotherapy due to nonlinearity at that point. OS stratified by year was examined using Kaplan-Meier and Cox regressions. P-values <0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Incidence of Stage I disease at diagnosis

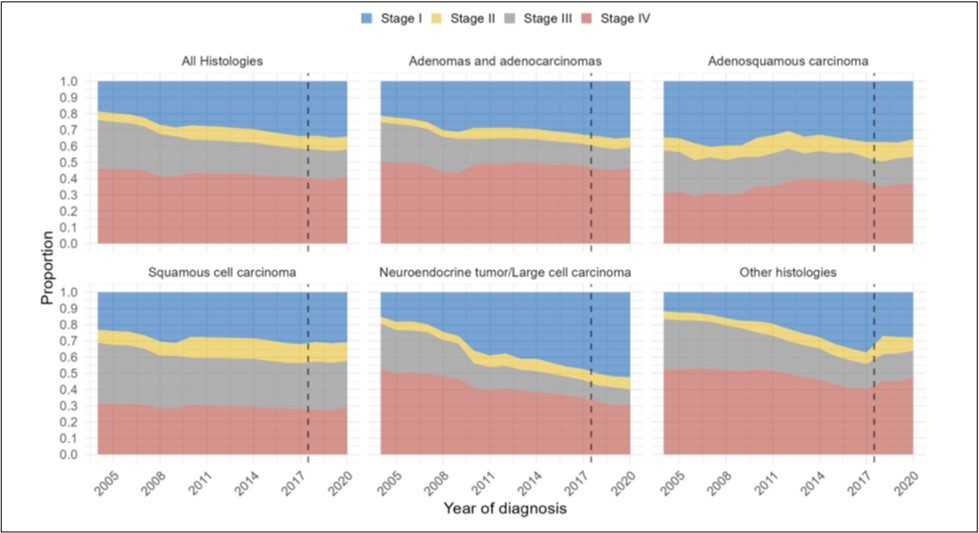

2,028,553 patients were identified with NSCLC (Supp.Table 2). Over the study period from 2004-2020, there was a 15% increase in patients with Stage I disease at diagnosis. Over time, patients were more likely to be diagnosed with Stage I disease (OR1.05, 95%CI 1.05-1.05, p<0.001) (Figure 1a) (Supp.Table 3).

The NSCLC cohort was grouped by adenocarcinoma, adenosquamous, neuroendocrine, squamous, and other histologies. Of patients with adenocarcinoma, there was a 14% increase in Stage I disease, and over time patients were more likely to be diagnosed with Stage I disease (OR1.03, 95%CI 1.03-1.04, p<0.001) (Figure 1b).

Of adenosquamous patients, there was a 2% increase in patients with Stage I disease at diagnosis. Over the study period, there was no significant change in stage (OR1.00, 95%CI 0.99-1.00, p=0.52) (Figure 1c). Incorporating the change in AJCC staging system in 2018, patients with adenosquamous histology were less likely to be diagnosed with Stage I disease prior to 2018 (OR0.99, 95%CI 0.98-1.00, p=0.018), and there was no significant change in Stage I after 2018 (OR0.97, 95%CI 0.90-1.05, p=0.41).

Of patients with squamous histology, there was a 8% increase in patients with Stage I disease at diagnosis. Over the study period, patients were more likely to be diagnosed with Stage I (OR1.02, 95%CI 1.02-1.02, p<0.001) (Figure 1d).

In patients with neuroendocrine and other histologies, there was a 37% and 16% increase in patients with Stage I disease, respectively. Over time, patients in both cohorts were more likely to be diagnosed with Stage I (Neuroendocrine: OR1.12, 95%CI 1.11-1.12, p<0.001; Other: OR1.12, 95%CI 1.11-1.12, p<0.001) (Figure 1e-f).

Figure 1.Distribution of clinical stage group over time by year of diagnosis from 2004-2020, for (A) all histologies of NSCLC, (B) adenocarcinomas, (C) adenosquamoushistology, (D) squamous histology, (E) neuroendocrine histology, and (F) other histologies. (Dotted line represents change in AJCC staging guidelines).

Incidence of NSCLC with well-differentiated or moderately-differentiated grade

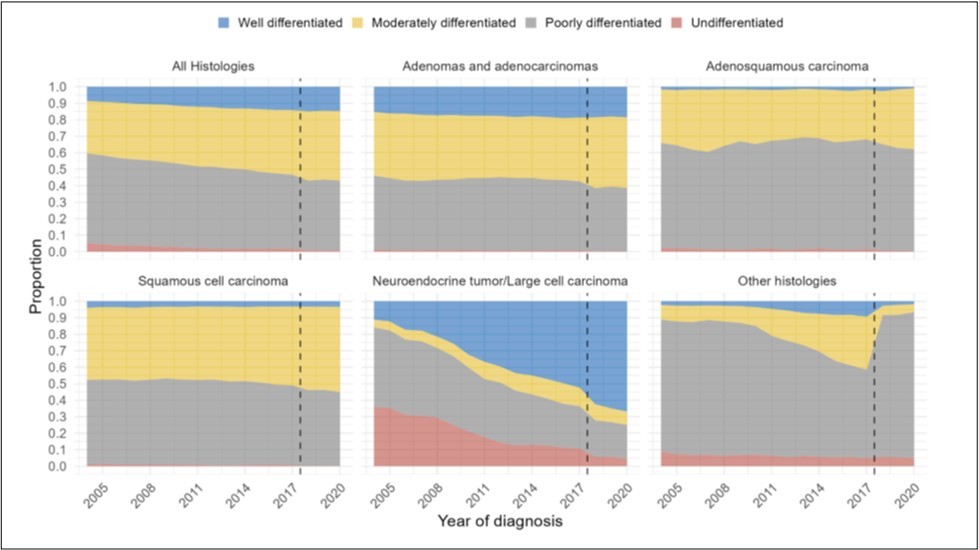

We next assessed the grade at diagnosis over time. Of 1,152,308 patients with NSCLC, there was a 17% increase in well-differentiated or moderately-differentiated histology at diagnosis. Over time, patients were more likely to have well-differentiated histology (OR1.04, 95%CI 1.04-1.04, p<0.001) (Figure 2a) (Supp.Table 4).

Of patients with adenocarcinoma, there was a 6% increase in patients with well- or moderately-differentiated histology at diagnosis, and over time patients were more likely to have well-differentiated histology (OR1.01, 95%CI 1.01-1.01, p<0.001) (Figure 2b).

Of patients with adenosquamous histology, there was a 4% increase in patients with well- or moderately-differentiated histology at diagnosis, but there was no significant change in grade (OR1.00, 95%CI 0.98-1.03, p=0.77) (Figure 2c). When accounting for the change in AJCC staging in 2018, there was still no significant change in grade before 2018 (OR1.01, 95%CI 0.98-1.04, p=0.57), but after 2018 patients were significantly less likely to be diagnosed with well-differentiated cancer (OR0.77, 95%CI 0.59-0.99, p=0.044).

Of patients with squamous histology, there was a 6% increase with well- or moderately-differentiated histology at diagnosis, but over time patients were less likely to be found to have well-differentiated histology (OR0.99, 95%CI 0.99-0.99, p<0.001) (Figure 2d). When accounting for the change in AJCC staging, there was a decrease in the likelihood of well-differentiated histology prior to 2018 (OR0.99, 95%CI 0.98-0.99, p<0.001), but no significant change after 2018 (OR1.02, 95%CI 0.96-1.08, p=0.50).

Of patients with neuroendocrine histology, there was a 57% increase in patients with well- or moderately-differentiated histology, and over time patients were more likely to be found to have well-differentiated histology (OR1.18, 95%CI 1.18-1.19, p<0.001) (Figure 2e).

Of patients with other histologies, there was a 3% decrease in patients with well- or moderately-differentiated histology, but patients were more likely to be found to have well-differentiated histology (OR1.09, 95%CI 1.08-1.10, p<0.001) (Figure 2e). When accounting for the change in AJCC staging, patients were more likely to have well-differentiated histology prior to 2018 (OR1.14, 95%CI 1.13-1.14, p<0.001), and patients were less likely to have well-differentiated grade after 2018 (OR0.80, 95%CI 0.66-0.96, p=0.015).

Figure 2.Distribution of grade over time by year of diagnosis from 2004-2020, for (A) all histologies of NSCLC, (B) adenocarcinomas, (C) adenosquamous histology, (D) squamous histology, (E) neuroendocrine histology, and (F) other histologies. (Dotted line represents change in AJCC staging guidelines).

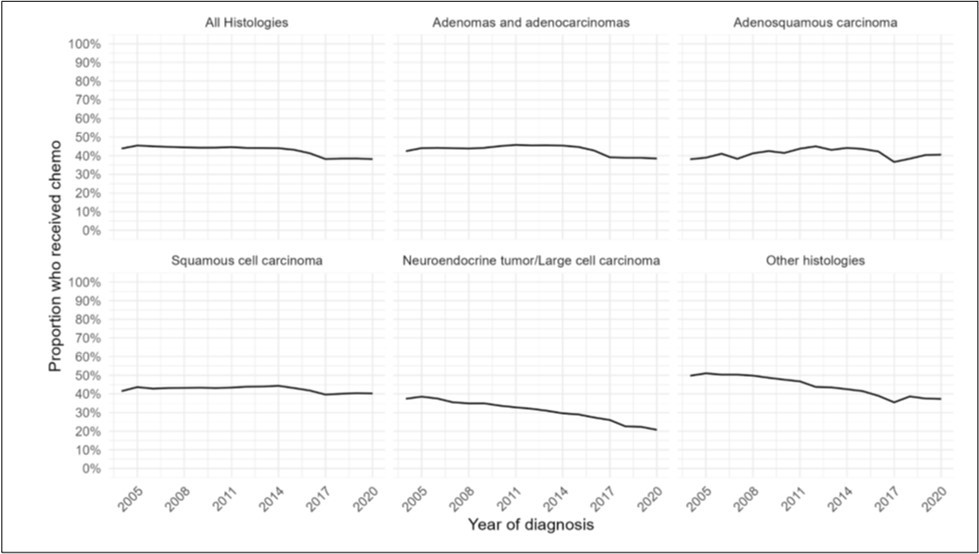

Non-targeted systemic treatment decreased

The cohort was evaluated for systemic chemotherapy use as first-line treatment. Of 1,980,499 NSCLC patients, there was a 6% decrease in systemic treatment, and patients were less likely to receive systemic treatment over time (OR0.98, 95%CI 0.98-0.98, p<0.001) (Figure 3a) (Supp.Table 5).

Of patients with adenocarcinoma, there was a 4% decrease in use of systemic treatment, and patients were less likely to receive systemic treatment over time (OR0.98, 95%CI 0.98-0.99, p<0.001) (Figure 3b).

Of patients with adenosquamous histology, there was a 3% increase in systemic treatment; however, there was no change in likelihood of use of systemic treatment (OR1.00, 95%CI 1.00-1.01, p=0.78) (Figure 3c).

Of patients with squamous histology, there was a 1% decrease in use of systemic treatment, and patients were significantly less likely to receive systemic treatment (OR0.99, 95%CI 0.99-0.99, p<0.001) (Figure 3d).

Of patients with neuroendocrine and other histologies, there was a 16% and 13% decrease in use of systemic treatment, respectively. Patients were less likely to receive systemic treatment over time (Neuroendocrine: OR0.95, 95%CI 0.95-0.95, p<0.001; Other: OR0.96, 95%CI 0.96-0.96, p<0.001) (Figure 3e-f).

Figure 3.Distribution of systemic chemotherapy usage over time by year of diagnosis from 2004-2020, for (A) all histologies of NSCLC, (B) adenocarcinomas, (C) adenosquamous histology, (D) squamous histology, (E) neuroendocrine histology, and (F) other histologies.

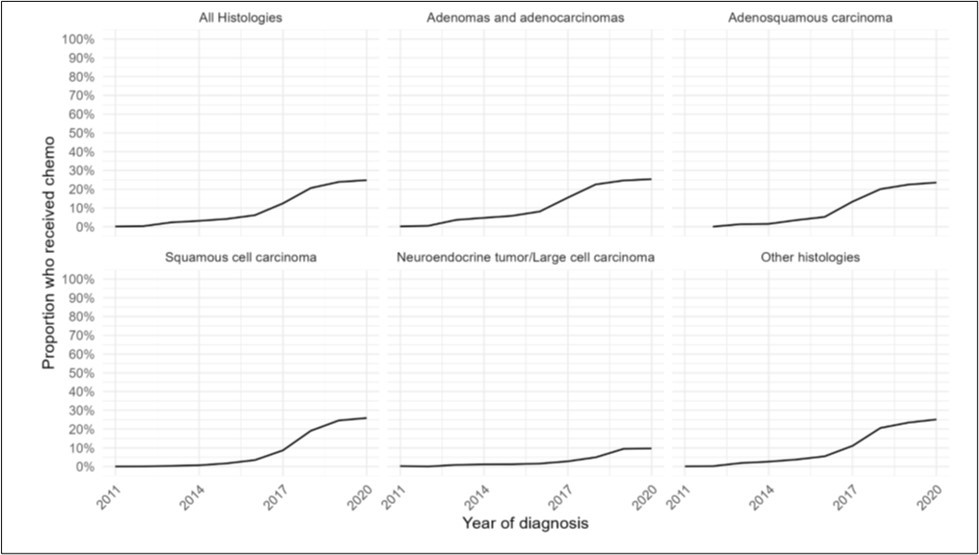

Use of immunotherapy increased drastically

The cohort was evaluated to assess use of immunotherapy. Of 1,265,149 NSCLC patients, there was a 24.8% increase in immunotherapy treatment from 2011-2020. Patients were more likely to receive immunotherapy over time (OR1.55, 95%CI 1.55-1.56, p<0.001) (Figure 4a) (Supp.Table 6). Although usage increased rapidly from 2011 to 2014 (OR 5.20), it increased but more slowly from 2014 to 2020 (OR1.50) (Supp.Fig.1a).

Of patients with adenocarcinoma, there was a 24.8% increase in use of immunotherapy. Patients were more likely to receive immunotherapy over time (OR1.47, 95%CI 1.46-1.47, p<0.001) (Figure 4b). Although usage increased rapidly from 2011 to 2014 (OR 5.69), it increased but more slowly from 2014 to 2020 (OR 1.40) (Supp.Fig.1b).

Of patients with adenosquamous histology, there was a 24% increase in use of immunotherapy over the study period. Patients were more likely to receive immunotherapy over time (OR1.63, 95%CI 1.59-1.68 p<0.001) (Figure 4c). Although usage increased rapidly from 2011 to 2014 (OR 28.0), it increased but at a slower rate from 2014 to 2020 (OR1.55) (Supp.Fig.1c).

Patients with squamous histology had a 25.9% increase in use of immunotherapy over time. Patients were more likely to receive immunotherapy over time (OR1.81, 95%CI 1.80-1.83, p<0.001) (Figure 4d). Although usage increased rapidly from 2011 to 2014 (OR 3.03), it increased but more slowly from 2014 to 2020 (OR1.76) (Supp.Fig.1d).

Of patients with neuroendocrine histology and other histologies, there was a 9.4% and 24.8% increase in immunotherapy over the study period, respectively. Patients were more likely to receive immunotherapy (Neuroendocrine: OR1.55, 95%CI 1.51-1.59, p<0.001; Other histologies: OR1.62, 95%CI 1.60-1.63, p<0.001) (Figure 4e-f). Although usage increased rapidly for these patients from 2011 to 2014 (Neuroendocrine: OR2.31; Other: OR4.94), it increased but more slowly from 2014 to 2020 (Neuroendocrine: OR1.55; Other: OR1.56) (Supp.Fig.1e-f).

Figure 4.Distribution of immunotherapy usage over time by year of diagnosis from 2011-2020, for (A) all histologies of NSCLC, (B) adenocarcinomas, (C) adenosquamous histology, (D) squamous histology, (E) neuroendocrine histology, and (F) other histologies.

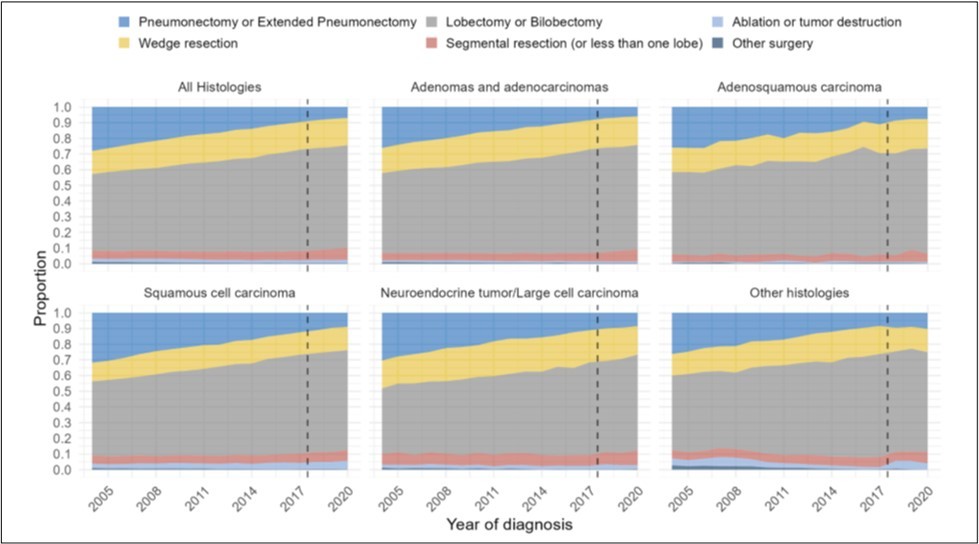

Pneumonectomies decreased in surgical patients with NSCLC

We assessed surgery performed over the study period. Of 596,409 NSCLC patients, there was a decrease in likelihood of receiving a pneumonectomy (OR0.90, 95%CI 0.90-0.91, p<0.001), but segmentectomies and wedge resections were only shown to increase by 4.4%, although the study was not powered to asses the statistical significance (Figure 5a) (Supp.Table 7).

Of adenocarcinoma patients, there was a decrease in surgery performed overall by 6%. There was a decrease in likelihood of receiving a pneumonectomy (OR0.90, 95%CI 0.90-0.90, p<0.001), but segmentectomies and wedge resections only increased by 5.1% over the study period (Figure 5b).

Of patients with adenosquamous histology, there was a decrease in likelihood of receiving a pneumonectomy (OR0.91, 95%CI 0.90-0.92, p<0.001) over the study period (Figure 5c), and the proportion of segmentectomies and wedge resections increased by 3.4%.

Of patients with squamous histology, there was a decrease in likelihood of receiving a pneumonectomy (OR0.91, 95%CI 0.91-0.91, p<0.001) (Figure 5d). This group had a decrease in segmentectomies and wedge resections by 4.5%.

Of patients with neuroendocrine and other histologies, there was a decrease in likelihood of receiving a pneumonectomy (Neuroendocrine: OR0.91, 95%CI 0.91-0.92, p<0.001; Other: OR0.91, 95%CI 0.90-0.91, p<0.001). Segmentectomies and wedge resections increased by 2.4% for neuroendocrine histology and 2.9% for other histologies (Figure 5e-f).

Figure 5.Distribution of type of surgical treatment performed over time by year of diagnosis from 2004-2020, for (A) all histologies of NSCLC, (B) adenocarcinomas, (C) adenosquamous histology, (D) squamous histology, (E) neuroendocrine histology, and (F) other histologies.

Overall Survival

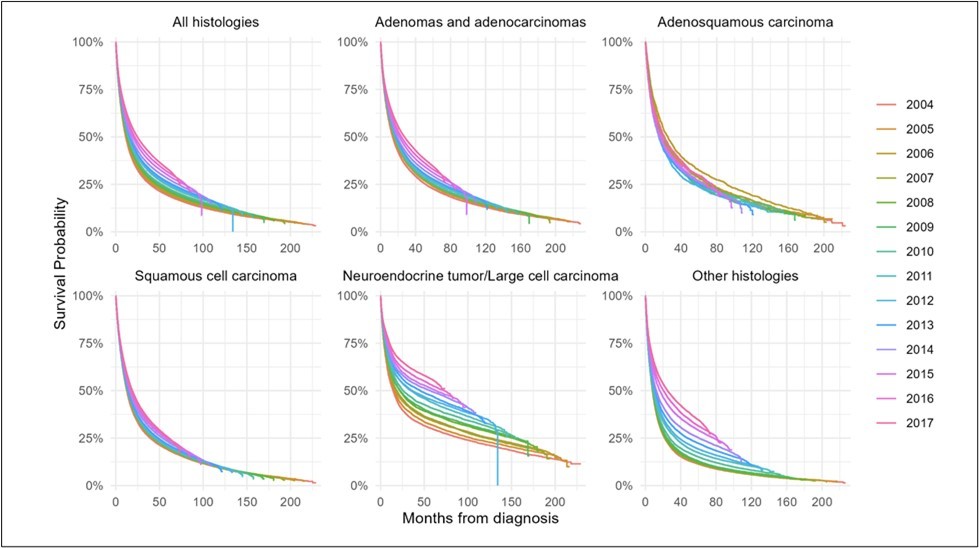

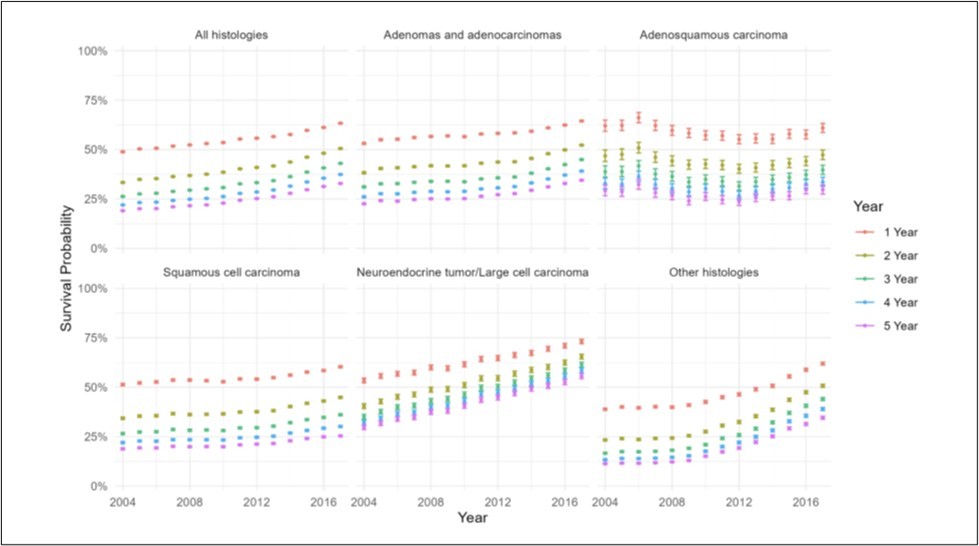

A 5-year survival analysis was performed to evaluate observed survival as an unadjusted temporal association. Cox regression was performed from 2011 through 2017. For the overall cohort, each subsequent year was associated with decreased risk of mortality (HR0.97/year, 95%CI 0.97-0.97, p<0.001) (Figure 6a) (Supp.Table 8). The estimated probability of survival for year of diagnosis increased over time (Figure 7a).

Of adenocarcinoma patients, each year was associated with decreased risk of mortality (HR0.98/year, 95%CI 0.98-0.98, p<0.001) (Figure 6b). Additionally, the estimated probability of survival for year of diagnosis increased over time (Figure 7b).

Of patients with adenosquamous histology, survival appeared consistent; however, later years of diagnosis were associated with slightly increased risk of mortality (HR1.01/year, 95%CI 1.00-1.01, p<0.001) (Figure 6c). The estimated probability of survival for year of diagnosis did not show a significant trend (Figure 7c).

Of patients with squamous histology, each subsequent year was associated with decreased risk of mortality (HR0.99/year, 95%CI 0.99-0.99, p<0.001) (Figure 6d). The probability of survival for year of diagnosis increased over time (Figure 7d).

Of patients with neuroendocrine and other histologies, each year was associated with decreased risk of mortality (Neuroendocrine: HR0.95/year, 95%CI 0.95-0.95, p<0.001; Other: HR0.95/year, 95%CI 0.95-0.95, p<0.001) (Figure 6e-f). In both groups the probability of survival for year of diagnosis increased over time (Figure 7e-f).

Figure 6.5 year overall survival by year of diagnosis from 2011-2020, for (A) all histologies of NSCLC, (B) adenocarcinomas, (C) adenosquamous histology, (D) squamous histology, (E) neuroendocrine histology, and (F) other histologies.

Figure 7.Probablility of survival by year of diagnosis from 2011-2020, for (A) all histologies of NSCLC, (B) adenocarcinomas, (C) adenosquamous histology, (D) squamous histology, (E) neuroendocrine histology, and (F) other histologies.

Discussion

From 2004 to 2020, NSCLC was increasingly diagnosed at earlier stages across histologies except adenosquamous. While stage at diagnosis improved, grade trends varied. Adenocarcinoma and neuroendocrine cases were more often well-differentiated, whereas adenosquamous, squamous, and other types were less so, potentially influenced by staging changes (Figure 8).

The rise in Stage I NSCLC diagnoses aligns with prior studies. Singareddy et al., among others, reported increases in early-stage cases, though notably excluded post-2018 patients.12, 13, 14 Our study extends the timeline beyond the AJCC staging update. The rise in Stage I diagnoses is likely due to increased CT scan use, particularly after the 2013 USPSTF recommendation for screening in high-risk adults.15, 16 Additionally, more early-stage lung cancers are being found incidentally during unrelated evaluations.17, 18, 19

Unlike other histologies, stage at diagnosis for adenosquamous histology was less often Stage I after 2018. Adenosquamous carcinoma is a rare NSCLC subtype (1-4% of cases; 1.3% in our cohort) and contains both squamous and adenocarcinoma components.20, 21, 22, 23 It is aggressive, usually diagnosed at higher stages, and has a worse prognosis than either histology alone. Its aggressiveness may stem from undifferentiated cells or the combination of two cancer types.23, 24, 25

This is the first study to examine histological grade over time. Tumor grade trends varied by histology, with adenocarcinoma and neuroendocrine showing more well-differentiated tumors, while others did not. The AJCC staging change impacted statistical significance when time periods were analyzed separately. Tumor grade is highly prognostic of overall survival and recurrence-free survival for all histological subtypes. It is important to understand if the lack of significance was associated with a survival change.26, 27 Despite limited grade shifts, survival improved, likely due to earlier diagnoses, better treatments, and surgical advances.

We found that patients were less likely to receive chemotherapy over time, except in adenosquamous cases. Since FDA approval, immunotherapy usage increased significantly, aligning with guidelines for advanced and, increasingly, earlier-stage disease. Molecular testing is now common across all stages to guide targeted therapy and immunotherapy. 3, 4, 5, 28, 29 While the NCDB combines targeted therapy and immunotherapy, limiting detailed analysis, it is clear these have transformed NSCLC care and improved survival.

We found a decline in pneumonectomies across all NSCLC groups. Pneumonectomy carries high risks such as bleeding, bronchopleural fistula, and death, and can lead to reduced lung function and other complications post-surgery.30, 31, 32 Earlier diagnosis as a result of screening has allowed for decreased need for pneumonectomies. Additionally, with neoadjuvant treatment now standard for Stage II and III disease, tumors may become easier to resect, reducing need for pneumonectomy. The rise of immunotherapy has further contributed to this trend by improving tumor resectability.

The increase of sublobar resection was smaller than expected, with all histological subtypes experiencing an increase in sublobar resection less than 5%. A prior analysis of the NCDB, limited to 2004 to 2013, showed a decrease in frequency of treatment with surgery.33 Surgery remains the mainstay of treatment for early-stage tumors and select locally-advanced tumors.4, 34, 35, 36 With advancements in thoracoscopic surgery and recent clinical trials showing non-inferiority of sublobar resections compared to lobectomies, it was expected that there would be an increase in sublobar resections.8, 9, 10, 37 Of note, the eligibility for sublobar resection cannot be determined in this database given that the database lacks tumor size, consolidation-to-tumor ratio, and radiologic characteristics. Therefore, some of these observations may reflect appropriate surgical selection rather than under-adoption.

The low rate of sublobar resections is likely multifactorial. Although minimally invasive techniques improve outcomes and visualization, many surgeons may lack experience with the new technology, complex segmentectomies and adequate lymphadenectomy.38 Additionally, insurance barriers, such as Medicaid not covering sublobar resections, limit use.39 These findings highlight the potential value of more specialized training—particularly at low-volume centers—and equitable insurance coverage for sublobar resections. A longer period may be necessary to see the uptake of sublobar resection on the national level.

This national database study has limitations. Although coding errors are possible, NCDB data are collected by trained abstractors, enhancing reliability.11 Radiation therapy was excluded due to insufficient patient numbers for meaningful evaluation. Immunotherapy and targeted therapy are combined into one variable in the NCDB, and therefore individual effects of these treatments are unable to be discerned. Large sample size may cause small effects to appear statistically significant, but consistent results and thorough checks support validity.

Conclusion

Over the study period, there was a significant trend towards increased diagnosis of Stage I NSCLC. Some treatment patterns evolved concordantly with guidelines, with more patients receiving immunotherapy as first-line treatment. Despite recommendations for sublobar resections, there was no notable increase in these procedures. Guidelines and treatment patterns should reflect the current landscape of lung cancer, including use of both sublobar resections for appropriate patients and targeted therapies as first-line treatment.

Disclosures

SS and KM received funding from NIH P01-CA254859. KW received funding from NIH T32-CA251063-05. WH and AW received funding from ACC support grant P30-CA016520.

Central message

In NCDB patients, more patients received immunotherapy and less received chemotherapy. Despite these changes, the frequency of sublobar resections remains stagnant, begging for widespread adoption.

Perspective statement

We found systemic treatment patterns evolved concordantly with guidelines. Despite recommendations for sublobar resections, there was no notable increase in sublobar resections. Guidelines and treatment patterns should reflect the current landscape of lung cancer, including use of both sublobar resections and targeted therapies as first-line treatment.

Supplementary Material

References

- 3.Meyer M-L. (2024) New promises and challenges in the treatment of advanced non-small-cell lung cancer.Lancet Lond. Engl.404.

- 4.Kim S. (2025) . The Society of Thoracic Surgeons Expert Consensus on the Multidisciplinary Management and Resectability of Locally Advanced Non-small Cell Lung Cancer.Ann.Thorac. Surg.119 .

- 5.G J Riely. (2024) Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer, Version 4.2024. , NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology.J. Natl.Compr. CancerNetw 22, 249-274.

- 6.Wolf A M D. (2024) Screening for lung cancer: 2023 guideline update from the American Cancer Society.CA. , Cancer J. Clin.74 50.

- 7.Altorki N. (2023) Lobar or Sublobar Resection for Peripheral Stage IA Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer.N. , Engl. J. Med.388 489.

- 8.Altorki N. (2024) segmentectomy, or wedge resection for peripheral clinical T1aN0 non–small cell lung cancer: A post hoc analysis. of CALGB 140503 (Alliance).J.Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg.167 338-347.

- 9.Saji H. (2022) Segmentectomy versus lobectomy in small-sized peripheral non-small-cell lung cancer (JCOG0802/WJOG4607L): a multicentre, open-label, phase 3, randomised, controlled, non-inferiority trial.The. Lancet399 1607-1617.

- 10.Hattori A. (2024) Segmentectomy versus lobectomy in small-sized peripheral non-small-cell lung cancer with radiologically pure-solid appearance in Japan (JCOG0802/WJOG4607L): a post-hoc supplemental analysis of a multicentre, open-label, phase 3 trial.Lancet Respir. Med.12.

- 11.D J Boffa. (2017) Using the National Cancer Database for Outcomes Research: A Review.JAMA Oncol.3. 1722-1728.

- 12.A L Potter. (2022) Association of computed tomography screening with lung cancer stage shift and survival in the United States: quasi-experimental study.BMJe069008. 10-1136.

- 13.S M Adnan. (2022) . Challenges in the Methodology for Health Disparities Research in Thoracic Surgery.Thorac. Surg. Clin.32 67-74.

- 14.Ganesh A. (2022) Increased Disparities in Patients Diagnosed with Metastatic Lung Cancer Following Lung CT Screening in the United States.Clin. Lung Cancer23.

- 15.Preventive U S. (2021) Services Task Force et al. Screening for Lung Cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement.JAMA325.

- 16.Koning H J De. (2020) Reduced Lung-Cancer Mortality with Volume CT Screening in a Randomized Trial.N. , Engl. J. Med.382 503.

- 17.Kocher F. (2016) Incidental Diagnosis of Asymptomatic Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer: A Registry-Based Analysis.Clin. Lung Cancer17. 62-67.

- 18.Quadrelli S. (2015) Clinical Characteristics and Prognosis of Incidentally Detected Lung Cancers.Int. , J. Surg. Oncol.2015 1.

- 20.Zhu L. (2018) Clinical characteristics and prognosis of patients with lung adenosquamous carcinoma after surgical resection: results from two institutes.J.Thorac. Dis.10 2397-2402.

- 21.W D Travis. (2015) . The 2015 World Health Organization Classification of Lung Tumors.J.Thorac. Oncol.10 1243-1260.

- 22.Uramoto H. (2010) Clinicopathological characteristics of resected adenosquamous cell carcinoma of the lung: Risk of coexistent double cancer.J.Cardiothorac. , Surg.5 92.

- 23.Takamori S. (1991) Clinicopathologic characteristics of adenosquamous carcinoma of the lung.Cancer67. 649-654.

- 24.Gawrychowski J. (2005) Prognosis and survival after radical resection of primary adenosquamous lung carcinoma.Eur. , J. Cardio-Thorac. Surg. Off. J. Eur. Assoc. Cardio-Thorac. Surg.27 686.

- 25.Nakagawa K. (1740) Poor prognosis after lung resection for patients with adenosquamous carcinoma of the lung.Ann.Thorac. Surg.75.

- 26.J A Barletta, Y. (2010) Prognostic significance of grading in lung adenocarcinoma.Cancer116. 659-669.

- 27.C K. (1982) Carcinoma of the Lung: Evaluation of Histological Grade and Factors Influencing Prognosis.Ann.Thorac. Surg.33.

- 29.Chevallier M. (2021) Oncogenic driver mutations in non-small cell lung cancer: Past, present and future.World.

- 30.Christodoulides N. (2023) Post-pneumonectomy syndrome: a systematic review of the current evidence and treatment options.J.Cardiothorac. Surg.18.

- 31.Kayawake H. (2018) Surgical outcomes and complications of pneumonectomy after induction therapy for non-small cell lung cancer.Gen.Thorac. , Cardiovasc. Surg.66 658.

- 32.Deslauriers J. (2011) Long-term physiological consequences of pneumonectomy.Semin.Thorac. , Cardiovasc. Surg.23

- 33.K E Engelhardt. (2004) et al Treatment trends in early-stage lung cancer in the United States. , Cardiovasc. Surg.156 1233-1246.

- 36.P E. (2017) Early and locally advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC): ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up.Ann. Oncol.28.