Dissociative Amnesia – A Challenge to Therapy

Abstract

The psychiatric disease of dissociative amnesia is described and illustrated with case reports. It is emphasized that dissociative amnesia has a stress or trauma-related etiology and that affected individuals, contrary to the still dominant clinical belief, are frequently more severely and enduringly affected. That means, most of them show severe retrograde amnesia for their biography, usually accompanied by changes in their personality and sometimes also by alterations in other cognitive and emotive domains. As many patients show the phenomenon of “la belle indifference”, their motivation for therapy or treatment of their amnesia is reduced. Patients also seem to a high degree to possess immature, unstable personality features. Nevertheless, a number of quite divergent, though largely not evidence-based, therapeutic approaches exist and are described. They are divided into (a) psychopharmacological and somatic treatments, (b) psychotherapeutic interventions, and (c) neuropsychological rehabilitation. Furthermore, detailed treatment strategies are provided.

Author Contributions

Academic Editor: Shuai Li, University of Cambridge, UK.

Checked for plagiarism: Yes

Review by: Single-blind

Copyright © 2018 Angelica Staniloiu, et al.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Competing interests

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Citation:

Introduction

Dissociative amnesia is characterized by amnesia in the episodic-autographical domain. Usually patients “forget” (or alternatively said: have no conscious access to) their total personal past.1,2 Semantic memory, which is memory for neutral facts, and procedural memory and priming (cf. Figure 2 in ref. 1 or the Figure in ref. 3)3 are usually preserved, implying that the patients on first glance appear quite normal: They can read, write, calculate, behave in a normal social way, and know details about the world and famous people. All the more their lack of access to their personal past appears puzzling to their social environments (partners, friends, etc.). In very rare cases the reverse amnesia picture may be true, namely a preservation of old episodic-autobiographical memories, but an inability to store new personal information long-term4,5. This may be accompanied by changes in other cognitive and emotive domains and may also lead to changes in personality.6,7,8 While it was stated in classical textbooks that the amnesia is usually transient and functional recovery will be complete, more recent research shows that patients with dissociative amnesia may remain amnesic for years and decades, though those with the retrograde version of dissociative amnesia can learn about their past in a neutral, emotionally distant manner.

Dissociative amnesia as a psychiatric condition has a long background, which reached increased awareness with Charcot, Janet, and Freud.9 At their time and even until after the Second World War it was labeled ‘hysteria’. Later it was termed psychogenic amnesia. This term has remained until today though its use is nowadays much rarer than that of dissociative amnesia.10 Other, closely related terms are ‘functional amnesia’,11 implying that the amnesia has a function for the patient, and ‘mnestic block syndrome’12 – indicating that the “forgotten” memories are not lost, but just blocked from access to consciousness and subsequently may at a later stage recover.

The etiology is regarded as being related to major stress and (psychic) trauma situations with which the individual could not cope properly.1,13,14,15 Such stress or trauma situations make individuals especially vulnerable, if they occur in childhood and youth and if there is later “revival” of such stress or trauma conditions in adult (or later) life (“two-hit hypothesis”, cf. ref. 1). For example, patients with a background in migration are frequently affected,16 which is a confirmation for the stress hypothesis of dissociative amnesia. Also, a forensic background can be found in a minority of the patients.1,2,11 Markowitsch17 proposed a model (cf. his Table 23.2), describing the likely etiology of dissociative amnesia and its possible alterations in the brain, which were investigated in a number of functional imaging studies, especially by using glucose positron emission tomography.6,18,19,20

Dissociative amnesia is considered, in comparison to many other psychiatric diseases, to be relatively rare, although prevalence rates have ranged between 0.2% and 7.3%, apparently depending on cultural background and methodology.1,2 Nevertheless, it has been diagnosed with increasing frequency. Recently two studies with comparatively large groups of patients with dissociative amnesia were published: one with 53 cases21 and one with 28 cases.22 With a few exceptions all patients in the study of Staniloiu et al.22 had persistent, long-lasting amnesia. Furthermore, many patients show a tendency towards depression and an affective predisposition, named since Janet and Freud “belle indifference”.8 The latter is coupled with apparently little caring about their future. While the condition of “la belle indifference” may contribute to the persistence of their amnesia, it cannot solely explain why a substantial number of patients remains in a long-lasting disease condition, which appears severe to the outsider. In order to address the question, why therapy frequently does not work or is not sought or pursued by the patients with this condition, we will first describe a few cases and then review the possible treatment or therapy modalities and their strengths and shortcomings.

Case Reports

Case A

This female patient in her mid-thirties became retrogradely amnesic for her last 14 years of life. She neither recognized her husband nor her three daughters. This occurred after the last of more than a dozen surgeries and hospitalizations, which the patient had undergone during the last 14 years. She awoke and stated that it is May 1989 instead of November 2003. Consequently (as in May 1989 still East and West Germany were separate states and also the Euro currency appeared only in 2002), she still calculated the finances in Deutschmarks, divided Germany in two countries and was astonished of the many articles available in supermarkets and of what she termed “clipped” cars in the street, that is of the Smarts (which indeed look as if they were clipped). However, her sense of familiarity (cf. the ‘perceptual memory system’ in Figure 2 in ref. 1 or in the Figure of ref. 3)3 seemed to have remained intact: She said that the person entering her room when she recovered from her last surgery looked like her husband, though she thought he must be much younger. She expected that her husband had no visible belly fat and that he had black instead of gray hair. More importantly she had some faint emotional feelings for her oldest daughter who was 15 years old, but no feelings for the two younger daughters. She always stated that she only knew of one daughter and that this one must be much younger than the one she dealt with.

While she stated that her childhood had been normal, this was not confirmed by collateral information. A friend of the patient called one of the authors 4 years later and revealed that the patient had had a difficult childhood with traumatizing experiences, such as nearly having been buried alive. The patient also had developed several further conversion symptoms in between, which however were transient and self-limited: She became half-sided paralyzed and blind on one eye (a symptomatology already described by Freud in 191023 (see also refs. 24, 25). In spite of her problems she refused therapy and remained amnesic even after several years.

Case B

As stated above, some patients with dissociative amnesia show a forensic background, which may become the trigger for the dissociative disturbance.26 This was the case for a man who had been accused of fraud amounting to millions of Euros. He had quit his job as a banker and promised his relatives and friends to increase the money they loaned him by high percentages. When the first clients wanted their money back, he became ill and was hospitalized with suspicion of a heart condition. During and after hospitalization he stated to have lost his past memories, including the memories for passwords of his computers. (The investigators were apparently unable to hack his computers.) He underwent a neuropsychological assessment in the context of dealing with court proceedings. While he participated to the evaluation without resistance, he showed a profound affective blunting. Even after his friend, who had accompanied him during testing, communicated to him after the end of the testing that his mother passed away, he displayed an affectless state. As mentioned above, already Janet27, 28 had described and labeled such behavior as “la belle indifference”.

It can be assumed that the stress accompanying his disloyal and illegal behavior (together with problems he had in his youth) triggered the dissociative condition, which then, on a background of accusation of fraud resulted in a persistent and severe condition. He showed ambivalence towards treatment and according to our knowledge did not pursue it.

Case C

This patient had several citizenships – a North and a South American and a Central European one. He had grown up in South America and co-owned a not very well running swimming pools business in the USA. He tended to conceal his sexual orientation (homosexuality) and often made trips with a female companion. He had deliberately engaged in a trip to foreign countries with a group of friends but prior to turning age 45 and having to take the flight back to his country of residence he flew into a state of dissociative fugue. During that state of dissociative narrowing of consciousness, he climbed a prominent mountain. Although he had no conscious recall of doing so, he suffered from inexplicable back pain and pain medications were found in his hotel room. He was identified and brought to Central Europe, because he there had best health insurance. He was not feeling comfortable being there with relatives and having to participate in psychotherapeutic treatment. He stated that he thought that the relatives wanted to confuse him or take advantage of him with their various versions of stories about his past. He only had trust in an old South American woman whom he named his aunt, although she was only an old friend of his family. His amnesia remained unchanged. He engaged in treatment with mistrust and then he interrupted it.

During an imaginative trauma psychotherapy session, he reportedly gained access to a few impressions of his mountain climbing experience in the company of a man. These however triggered strong anxiety feelings, non-sense images and a state of hypervigilance, the reason for which the psychotherapy sessions were stopped.

It can be assumed that his childhood and youth had been stressful due to the changing life conditions with different relatives, different languages, and different morals and manners (cf. the above-mentioned “two-hit hypothesis” and the trauma model for dissociative or psychogenic or functional amnesia).

Case D

This man in his 50ies was found sitting on a park bank without knowing who he was and where he belonged to. He was brought into a psychiatric clinic where he was diagnosed as probably having a psychogenic fugue (a dissociative amnesic condition accompanied by leaving the usual place of living, presently subsumed under ‘dissociative amnesia’). He was convinced to provide a photo of himself for the press in order to find out who he was. Due to this, his identity was revealed and he was brought into his home city and treated there in a university clinic.

A journalist from a prominent magazine contacted him and did an investigation on his past life. He found that the patient had been an orphan and had apparently been maltreated in several institutions. During his third adoption his parents wanted him to learn to play piano which he hated. He chopped himself several finger tips off in order to no longer have to play. Apparently, he was sexually abused by priests while attending a boarding school. In his later life he worked as a tourist guide in North Africa. Due to therapy or because of other conditions some of his early childhood memories came back; most of his past, however, remained inaccessible to him even after years.

Cases E and F

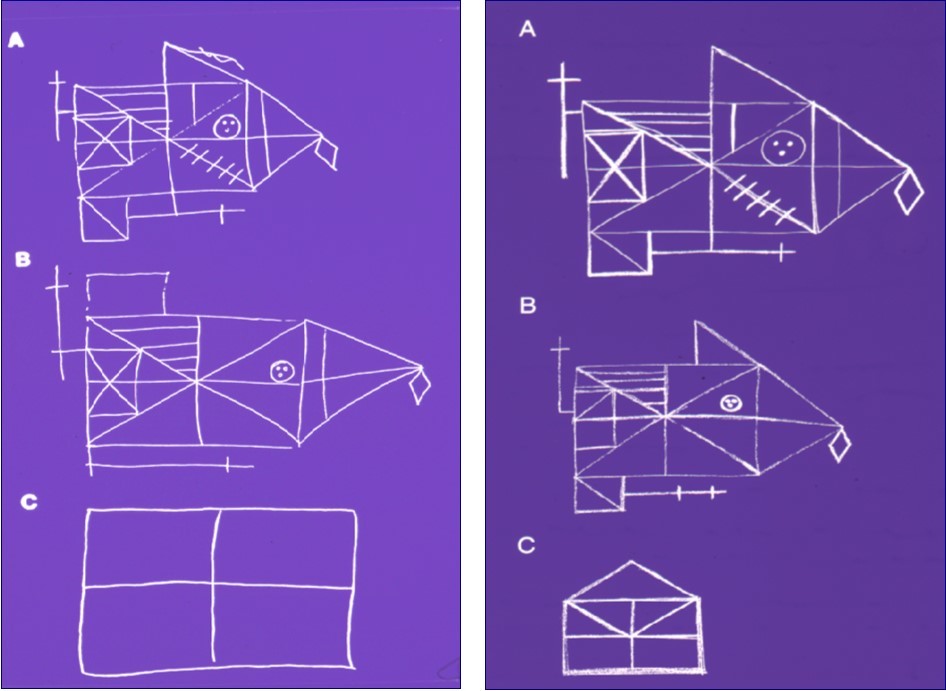

We studied two patients with the rare condition of anterograde dissociative amnesia.1 One patient was published in Markowitsch et al.29 and the other in Markowitsch and Staniloiu.5 The first patient29 was a 27-years old law student, who had had two consecutive car accidents with whiplash injury. She became anterogradely amnesic after the second accident and remained so from 1997 until the present. She had – under low cognitively demanding conditions – an anterograde memory span of four hours, which diminished to less than one hour under high demanding cognitive loading (with constant intensive memorizing). For instance, she behaved well above the norm in usual tests of memory such as the revised version of the Wechsler Memory Scale, as these tests have no retrieval delays beyond half an hour. She was able to copy the Rey-Osterrieth Figure: however, when asking her to reproduce it by heart after half an hour, one hour and two hours, respectively, she after one hour showed a rudimentary free recall (Figure 1) and after 2 hours she basically showed a nil free recall. This pattern was found in a testing session that took part three years after becoming amnesic and in another session that occurred five years after the onset of amnesia.

Figure 1.Performance of the anterogradely amnesic patient E in the so-called Rey-Osterrieth Figure, a complex drawing which the patient had to draw repeatedly. The patient first is shown the figure and has to draw it from the original (A). Thereafter she had to draw it a second time by heart after half an hour(B), then a third after an hour (C), and finally a fourth time after 2 hours (E was unable to reproduce it then). Patient E performed the test 3 years (left half of the figure) and 5 years (right half) after amnesia onset. Patient E was able to copy the figure without problems (A), she also was considerably above average when drawing it by heart after half an hour (B); but then, after a further half hour her performance was massively below expectation, and after 2 hours she – on both occasions – did not even remember having drawn the picture.

Patient E had superior memory for personal and general events from the time prior to amnesia onset which was tested in great detail. It also was found that the reference point for conscious recall coincided in time with her second car injury. However, aside from whiplash injury, brain scan results remained inconspicuous.

The same held true for patient F, who had two identical incidents during his work. He had been a nine-year old child, when his parents had sent him to live with relatives in another country (He moved from Bulgaria to East Germany). Though he did not understand any word in his new country, he adapted, finished school and became an engineer. After the re-unification of Germany, he lost his job and had to work as a distributor for cigarettes, where he had to fill vending machines. His wife told that he hated this job. On two occasions, separated by several years, cigarettes fell out from the vending machines and while he grabbed them to put them back into the machines, the door of the vending machine hit his head and he apparently became unconscious for very short periods of time. Thereafter he panicked, thinking that his money or his car were stolen, which, however, was not the case. Nevertheless, after the second incident he became anterogradely amnesic and remained so since then.

Similar to patient E, his memory span was about four hours. Interestingly, a memory span of four hours had also been described in another patient with a similar condition of psychogenically caused anterograde amnesia.30

While patient E refused therapy for her amnesia, patient F made some attempts (motivated by his wife) but gave up after some sessions.

Discussion and Implications for Therapy

The studying of the above presented cases was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Department of Psychology of the University of Bielefeld and conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all participants. The above presented cases were selected to show the diversity in background and etiology of patients with dissociative amnesia. Nevertheless, they demonstrate some commonalities: All patients in principal showed no or only minor recovery of their memory deficits, all of them refused or interrupted or did not appreciate the therapeutic sessions in which they participated. None of them had significant brain damage.

These case reports demonstrate that patients with dissociative amnesia show a low motivation for treatment. They usually have had a difficult background which started early in life. It is known that adverse life conditions in childhood and youth can lead to major problems in later life, especially if the respective individuals failed to develop adequate coping strategies.31,32,33,34 Genetic predispositions and epigenetic constellations may intensify adverse effects, leading, for example, to stress-related clinical conditions.35,36,37,38,39 Adverse life conditions during childhood have direct consequences on brain development.40

Davis et al.41studied more than 8700 twins for a general cognitive factor “g”. They found that this g-factor was at around age six related to heritability by 23%, and to environment by 74%. However, already about 7 or 8 years later the conditions had reversed: now 62% were attributed to genetics, and only 33% to environment, indicating that gene expression “explodes” during childhood and that consequently much care should be devoted to enable proper childhood experiences.

This is also reinforced by the fact that the child’s brain develops slowly during childhood and depending on environmental stimulation. Some brain regions within the frontal lobe even change until about age 2240 and for fiber systems such as the uncinate fascicle (which interconnects the frontal and anterior temporal lobes and is implicated in synchronizing emotional colorization with memory) a process of maturation increase has been found even after age 30.42 In maltreated and neglected children, as well as in monkeys growing up without their mothers, similar brain changes in the frontal and cingulate cortex were reported.43,44 There exist not only direct correlations between traumatic experiences and high levels of stress,11,45 but also correlations between negative experiences in childhood and changes in the brain.46,47,48,49,50,51 Such changes are not only related to an increase in the stress hormone levels, but also to a chronic decrease in the level of binding, prosocial hormones: as Fries et al.52 showed, orphans who had been adopted by caring parents, still manifested significantly lower oxytocin and vasopressin levels after years after adoption, compared to children who from the beginning of their life grew up with nurturing families.

These findings demonstrate that stress and trauma experiences during childhood have severe and long-lasting consequences on brain and behavior during later life. It should consequently be not too surprising – especially also not given the data from genetics and epigenetics – that behavioral constellations are difficult to change or to break once they are established (cf., e.g., the findings from Davis et al.41). One of the authors of the study on binding hormones in children52 stated in a TV interview that once the conditions are set in early childhood, they cannot be changed (“treated”), as a bullet cannot change its direction after it has left the gun. We nevertheless do not wish to and are far away from embracing a stance of generalizing negative effects in patients and therefore will discuss the current treatments as well as possibilities for novel treatment and therapy, which may open a pathway of hope in this condition.

Therapeutic Approaches

In general, there are three groups of possible therapeutic approaches for patients with dissociative amnesia, though no evidence-based therapy studies exist for this patient group1:

Psychopharmacological and somatic treatments for dissociative amnesia

Psychotherapeutic interventions for dissociative amnesia

Neuropsychological rehabilitation for dissociative amnesia

Psychopharmacological and Somatic Treatments

Somatic therapies consist in the prescription of anti-depressants (tricyclic antidepressants or selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors) in order to rise their mood status and to support psychotherapeutic approaches,19,30 with positive results. Barbiturates or benzodiazepines had been employed for drug-assisted interviews.53 Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) in combination with a serotonin noradrenalin re-uptake inhibitor antidepressant was reportedly successful in a case of dissociative fugue.54 However, in another case, ECT treatment precipitated an episode of persistent anterograde dissociative amnesia.55

Furthermore, there is – though very rarely applied – the so-called sodium amytal abreaction. This consists of injecting a barbiturate which should lower existing resistances and let the patient retrieve his or her autobiographical memories. Stuss and Guzman,56 several decades ago, described a patient for whom this therapy worked at least short-term (namely for the time, the drug was effective). One possibility why this treatment is rarely used is the possible side-effect of respiratory depression.1

Psychotherapeutic Interventions

On the psychotherapeutic site, there is conventional psychotherapy (cognitive-behavioral therapy, psychodynamic therapy), hypnosis, or Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR). Most therapeutic approaches follow a specified – more holistic – scheme which starts with an attempt to stabilize the personality. This seems to be important, as it is indeed an established observation that patients with dissociative amnesia frequently have a more fragile, insecure personality with low self-esteem (making them prone to influences from others). Personality stabilization also helps to motivate the patient to participate in therapy and to establish a psychosomatic model of his or her illness.1 Improvement of well-being seems to be crucial as well as a prerequisite for starting specific therapy.

In fact, more modern approaches of therapy in patients with dissociative amnesia focus not so much on reinstating forgotten memories, but emphasize the patient’s future well-being. These approaches are based on the assumption that it is better for the patient to deal with his or her future life and future perspectives in his or her daily living and environment, than to reinstall old – and in many instances negatively connotated – memories. Such an approach parallels that of Barbara Wilson57 for patients with brain damage. She stated that neuropsychological rehabilitation is more than cognitive rehabilitation, being “concerned with the amelioration of cognitive, emotional, psychosocial, and behavioural deficits caused by an insult to the brain” (p. 141).57

In spite of increasing data showing consistent brain imaging changes in patients with dissociative amnesia,6,20 it has been hard in lay, scientific and clinical world to completely move beyond the psychogenic-organic dichotomy. Albeit that there is nowadays increased recognition that cognition, emotion and psychosocial functioning are connected and “should be targeted by rehabilitation” (p. 14157; see also refs. 58 and 59), the treatment of dissociative amnesia continues to mainly take part in psychiatric or psychotherapeutic settings.60 In these settings, several somatic and psychotherapeutic interventions have been used to treat patients with dissociative amnesia, with one of the main objectives being the recovery of the “forgotten” memories.53

Several psychotherapeutic or combined treatment approaches were reported to yield favorable outcomes. However, various methodological weaknesses (e.g. small sample size, lack of a control group, limited or poorly standardized measures, and limited follow up period) make data difficult to interpret.19,30,60In 2000, Markowitsch and colleagues19 described the case of a 23-year old man with dissociative retrograde and partly anterograde amnesia, who was successfully treated with a combination of antidepressant and supportive psychotherapy. The reinstatement of his “lost” memories and of his capacity for consciously forming new memories was accompanied by a normalization of the glucose metabolism in his cerebrum, as evidenced by glucose PET. Smith et al.30 described the case of a 51-year old woman with anterograde psychogenic amnesia, whose condition improved with antidepressant (escitalopram), sleep interruption at 4 hours interval and supportive psychotherapy. Hypnosis has been used to facilitate the restoration with blocked memories, with variable results.53 The use of hypnotic techniques has recently been guided by the idea that similar neurobiological mechanisms might underlie both hypnosis and dissociative (conversion) disorders.61,62 Typically, a phasic treatment approach is employed in dissociative amnesic conditions, which encompasses as main early tasks the development of symptom management skills, modulation of dissociation and securing safety.53,60 The treatment is guided by the psychological trauma paradigm. A later phase has been named the “metabolism of trauma” and has as aims “remembrance” and “mourning”.63,64,65 The reconnection phase65 has as goals integration/ resolution, new coping skill learning, solidifying and maintaining gains.

Neuropsychological Rehabilitation

Data on neuropsychological rehabilitation for dissociative amnesia are sparse. They come mainly from cases of functional amnesia, which were characterized by a mixture of “organic” and “psychological” factors.66 They suggest that preserved implicit management of information66,67 may be used to improve the substantial disability associated with dissociative amnesia and quality of life.68 The neurorehabilitation treatment should be attempted cautiously, in collaboration with mental health treatment providers, who can help with modulating affective responses and preserving and monitoring safety.

Response to Current Treatments and Suggestions for Future Directions

Dissociative amnesias have a high variability with respect to recovery. Many cases of dissociative amnesia follow a chronic course, constituting a major source of disability.68

We therefore propose that there is currently a stringent need for:

Developing a broad theoretical framework57,69,70 for rehabilitation of dissociative amnesia.

Adopting a holistic approach71,72,73,74,75 that should aim towards achieving optimal physical, psychological, social and vocational wellbeing.69,70 This holistic approach, involving an enriched therapeutic milieu,76 may show benefits even if years passed after the onset of amnesia,74,77, 78 or, in the worst scenario it may prevent further cognitive deterioration due to lack of intellectual stimulation.79

Establishing a partnership between patients, their families and a multidisciplinary professional team with respect to selecting goals for rehabilitation that are SMART (specific, measurable, achievable, realistic and timely).57

Shifting the focus of treatment from the reinstatement of “forgotten” memories to developing strategies or skills that could help with functional adaptation in everyday life and environment and accomplishing selected goals.

The remediation of executive functions, which are often impaired in these population (6), could be of great importance for a variety of instrumental activities of daily living, interpersonal functioning, theory of mind functions, prospective memory rehabilitation and even for the facilitation of the episodic-autobiographical memory retrieval.74, 80

Making use of ecologically valid assessment methods81,82 and employing training methods that might allow generalization to the real world are important.83,84,85,86

For patients with functional amnesia with anterograde memory impairments externally directed assisted devices might be helpful84,86,87,88 with assisting with reducing every day memory and planning problems.

Social problem-solving interventions, metacognitive training and retraining of theory of mind functions might also be helpful for improving interpersonal relationships, community functioning and the sense of self-efficacy.74, 89

Finally, one may think of the availability of web or internet-based therapies for patients with dissociative amnesia, as they are at present already existing, for example, for patients with mild traumatic brain injury,90,91,92 a condition that is also observed in patients with dissociative amnesia.5,11,93

In addition, quality improvement of therapies can be done with support of internet-based technologies.94 Mindfulness-based training or therapy programs, which at present are available in the web for people with physical or psychiatric health conditions,95 could also be implemented for supporting therapeutic change in patients with dissociative amnesia.

Internet-based self-help and peer-support programs may aid the recovery process in patients with dissociative amnesia96,97,98,99 and a migration background.100

Internet-mediated social support and web-based acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) may offer additional help for stabilizing and grounding the personality,101,102,103,104 a factor of outstanding importance for treating patients with dissociative amnesia.8,11

References

- 2.Staniloiu A.Markowitsch HJ (2015) Amnesia psychogenic. International Encyclopedia of the Social and Behavioral Sciences (Vol. 13: Behavioral and Cognitive Neuroscience InJDWright (Ed.) , Oxford 651-658.

- 4.H J Markowitsch, Kessler J, Kalbe E, Herholz K. (1999) Functional amnesia and memory consolidation. A case of persistent anterograde amnesia with rapid forgetting following whiplash injury. , Neurocase 5, 189-200.

- 5.H J Markowitsch, Staniloiu A. (2013) The impairment of recollection in functional amnesic states. , Cortex 49, 1494-1510.

- 6.Brand M, Eggers C, Reinhold N, Fujiwara E, Kessler J. (2009) Functional brain imaging in fourteen patients with dissociative amnesia reveals right inferolateral prefrontal hypometabolism. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging Section. 174, 32-39.

- 7.Reinhold N, H J Markowitsch. (2007) Emotion and consciousness in adolescent psychogenic amnesia. , Journal of Neuropsychology 1, 53-64.

- 8.Reinhold N, H J Markowitsch. (2009) Retrograde episodic memory and emotion: a perspective from patients with dissociative amnesia. , Neuropsychologia 47, 2197-2206.

- 10.DSM-5. (2013) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5thed). American Psychiatric Association. , Washington, DC, USA

- 11.H J Markowitsch, Staniloiu A. (2016) Functional (dissociative) retrograde amnesia. In M Hallett JStone and A Carson (Eds.), Handbook of Clinical Neurology (3rdseries): Functional neurological disorders, Elsevier Amsterdam 419-445.

- 12.H J Markowitsch. (2002) Functional retrograde amnesia – mnestic block syndrome. , Cortex 38, 651-654.

- 14.C J Dalenberg, Brand B L, D H Gleaves, M J Dorahy, R J Loewenstein. (2012) Evaluation of the evidence for the trauma and fantasy models of dissociation. , Psychological Bulletin 138, 150-188.

- 15.Kloet E R de, Rinne T. (2007) Neuroendocrine markers of early trauma. In E Vermetten MJ Dorahy D Spiegel (Eds.), Traumatic dissociation. Neurobiology and treatment. American Psychiatric Publ , Arlington, VA, USA 139-156.

- 16.Staniloiu A, Wahl-Kordon A, H J Markowitsch. (2017) Dissoziative Amnesie und Migration. Zeitschrift für. , Neuropsychologie/Journal of Neuropsychology 26, 81-95.

- 17.H J Markowitsch. (2000) Repressed memories. In E. Tulving (Ed.),Memory, consciousness, and the brain: The Tallinn conference,Psychology Press. , Philadelphia, PA, USA 319-330.

- 18.H J Markowitsch, Kessler J, Ven C Van der, Weber-Luxenburger G, Heiss W-D. (1998) Psychic trauma causing grossly reduced brain metabolism and cognitive deterioration. , Neuropsychologia 36, 77-82.

- 19.H J Markowitsch, Kessler J, Weber-Luxenburger G, Ven C Van der, Albers M. (2000) Neuroimaging and behavioral correlates of recovery from mnestic block syndrome and other cognitive deteriorations. , Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychology and Behavioral Neurology 13, 60-66.

- 20.Staniloiu A, Vitcu I, H J Markowitsch. (2011) Neuroimaging and dissociative disorders. In V. Chaudhary (Ed.), Advances in brain imaging , INTECH – Open Access Publishers 11-34.

- 21.N A Harrison, Johnston K, Corno F, S J Casey, Friedner K. (2017) Psychogenic amnesia: syndromes, outcome, and patterns of retrograde amnesia. , Brain 140, 2498-2510.

- 22.Staniloiu A, H J Markowitsch, Kordon A. (2018) Psychological causes of amnesia: A study of 28 cases. , Neuropsychologia 110, 134-147.

- 23.Freud S. (1910) Die psychogene Sehstörung in psychoanalytischer Auffassung. , Ärztliche Fortbildung 9, 42-44.

- 24.Burgmer M, Konrad C, Jansen A, Kugel H, Sommer J. (2006) Abnormal brain activation during movement observation in patients with conversion paralysis. , NeuroImage 29, 1336-1343.

- 25.Magnin E, Thomas-Anterion C, Sylvestre G, Haffen S, Magnin-Feysot V. (2014) Conversion, dissociative amnesia, and Ganser syndrome in a case of "chameleon" syndrome: anatomo–functional findings. , Neurocase 20, 27-36.

- 26.C G Jung. (1902) Ein Fall von hysterischem Stupor bei einer Untersuchungsgefangenen. , Journal für Psychologie und Neurologie 1, 110-122.

- 28.Janet P. (1907) The Major Symptoms of Hysteria:. , Fifteen Lectures Given in the MedicalSchoolofHarvardUniversity.Macmillan,NewYork,NY,USA

- 29.H J Markowitsch, Kessler J, Kalbe E, Herholz K. (1999) Functional amnesia and memory consolidation. A case of persistent anterograde amnesia with rapid forgetting following whiplash injury. , Neurocase 5, 189-200.

- 30.C N Smith, J C Frascino, D L Kripke, P R McHugh, G J Treisman. (2010) Losing memories overnight: A unique form of human amnesia. , Neuropsychologia 38, 2833-2840.

- 31.J A Golier, Yehuda R, S J Lupien, P D Harvey, Grossmann R. (2002) Memory performance in holocaust survivors with posttraumatic stress disorder. , American Journal of Psychiatry 159, 1682-1688.

- 32.S J Lupien, B S McEwen, M R Gunnar, Heim C. (2009) Effects of stress throughout the lifespan on the brain, behavior and cognition. , Nature Reviews Neuroscience 10, 434-445.

- 33.S J Lupien, F S Maheu. (2000) Memory and stress.InFinkH(Ed.). Encyclopedia of Stress Elsevier Amsterdam.(Vol.2 F-N).(2nded.),(pp 693-699.

- 34.S E Mock, S M Arai. (2011) Childhood trauma and chronic illness in adulthood: mental health and socioeconomic status as explanatory factors and buffers. Frontiers in Psychology 1, 1-6.

- 35.Jovanovic T, K J Ressler. (2010) How the neurocircuitry and genetics of fear inhibition may inform our understanding of PTSD. , American Journal of Psychiatry 167, 648-662.

- 36.R G Parsons, K J Ressler. (2013) Implications of memory modulation for post-traumatic stress and fear disorders. , Nature Neuroscience 16, 146-153.

- 37.Arseneault L, Cannon M, H L Fisher, Polancyk G, T E Moffitt. (2011) Childhood trauma and children ‘s emerging psychotic symptoms: A genetically sensitive longitudinal cohort study. , American Journal of Psychiatry 158, 65-72.

- 38.Dolinoy D C, J R Weidman, R L Jirtle. (2007) Epigenetic gene regulation: linking early developmental environment to adult disease. , Reproductive Toxicology 23, 297-307.

- 39.P E Lutz, andTurecki G. (2014) DNA methylation and childhood maltreatment: from animal models to human studies. , Neuroscience 264, 142-156.

- 40.H J Markowitsch, Welzer H. (2010) The Development of Autobiographical Memory.PsychologyPress. , Hove, UK

- 41.Davis O S P, Haworth C M A, Plomin R. (2009) Dramatic Increase in heritability of cognitive development from early to middle childhood. An 8-year longitudinal study of 8,700 pairs of twins. , Psychological Science 20, 1301-1308.

- 42.Lebel C, Walker L, Leemans A, Phillips L, Beaulieu C. (2008) Microstructural maturation of the human brain from childhood to adulthood. , Neuroimage 40, 1044-1055.

- 43.Brito S A De, Mechelli A, Wilke M, K R Laurens, A P Jones. (2009) Size matters: Increased grey matter in boys with conduct problems and callous-unemotional traits. , Brain 132, 843-852.

- 44.Spinelli S, Chefer S, Suomi S J, J D Higley, C S Barr. (2009) Early-life stress induces long-term morphologic changes in primate brain. , Archives of General Psychiatry 66, 658-665.

- 45.H J Markowitsch. (2006) Brain imaging correlates of stress-related memory disorders in younger adults. , Biological Psychiatry and Psychopharmacology 8, 50-53.

- 46.R J Blair.(2013)The neurobiology of psychopathic traits in youths.Nature. , Reviews Neuroscience 14, 786-799.

- 47.A L Breeden, E M Cardinale, Lozier L M, J W VanMeter, Marsh.AA (2015)Callous-unemotionaltraits drive reduced white-matter integrity in youths with conduct problems.Psychological. , Medicine 19, 1-14.

- 48.Contreras-Rodríguez O, Pujol J, Batalla I, B J Harrison, Soriano-Mas C.. (2014)Functional connectivity bias in theprefrontalcortex of psychopaths.Biological Psychiatry 78, 647-655.

- 49.Fairchild G, Hagan C C, Walsh N D, Passamonti L, A J Calder.. Goodyer IM (2013)Brain structure abnormalities in adolescent girls with conduct disorder.Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 54, 86-95.

- 50.Marsh A A, Finger E C, DGV Mitchell, Reid M E, Sims C. (2008) Reduced amgdala response to fearful expressions in children and adolescents with callous-unemotional traits and siruptive behavior disorders. , American Journal of Psychiatry 165, 712-720.

- 51.G L Wallace, S F White, Robustelli B, Sinclair S, Hwang S.(2014).Cortical and subcortical abnormalities in youths with conduct disorder and elevatedcallous-unemotionaltraits.Journal of the. , American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 53, 456-465.

- 52.A B Fries, T E Ziegler, J R Kurian, Jacoris S, S D Pollak. (2005) Early experience in humans is associated with changes in neuropeptides critical for regulating social behavior. , Proceedings of the National Academy of the U. S. A 102, 17237-17240.

- 53.J R Maldonado, Spiegel D. (2008) Dissociative disorders. In RE Hales, SC Yudofsky, GO Gabbard(Eds.),The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Psychiatry (5thed.). American Psychiatric Publ , Arlington, VA, USA .

- 54.Kosidou K, Lindholm S. (2007) A rare case of dissociative fugue with unusually prolonged amnesia successfully resolved by ECT. , European Psychiatry 22, 264.

- 55.Kumar S, S L Rao, Sunny B, Gangadhar B. (2007) Widespread cognitive impairment in psychogenic amnesia. , Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences 61, 583-586.

- 56.D T Stuss, D A Guzman. (1988) Severe remote memory loss with minimal anterograde amnesia: A clinical note. , Brain and Cognition 8, 21-30.

- 57.B A Wilson. (2008) Neuropsychological rehabilitation. , Annual Reviews in Clinical Psychology 4, 141-162.

- 58.Brand M, Kalbe E, L W Kracht, Riebel U, Münch J. (2004) Organic and psychogenic factors leading to executive dysfunctions in a patient suffering from surgery of a colloid cyst of the Foramen of Monro. , Neurocase 10, 420-425.

- 59.H J Markowitsch. (1996) Organic and psychogenic retrograde amnesia: two sides of the same coin?. , Neurocase 2, 357-371.

- 60.Brand B L, Classen C C, S W McNary, Zaveri P. (2009) A review of dissociative disorders treatment studies. [Comparative Study Review]. , Journal of Nervous Mental Disorders 197, 646-654.

- 61.Bell V, D A Oakley, P W Halligan, Deeley Q. (2011) Dissociation in hysteria and hypnosis: evidence from cognitive neuroscience. , Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry 82, 332-339.

- 62.Mendelsohn A, Chalamish Y, Solomonovich A, Dudai Y. (2008) Mesmerizing memories: brain substrates of episodic memory suppression in posthypnotic amnesia. , Neuron 57, 159-170.

- 63.R P Kluft. (1990) Dissociation and subsequent vulnerability: A preliminary Study. , Dissociation 3, 167-173.

- 64.R P Kluft. (2007) The older female patient with a complex chronic dissociative disorder. , Journal of Women & Aging 19, 119-137.

- 66.E C Miotto. (2007) Cognitive rehabilitation of amnesia after virus encephalitis: a case report. , Neuropsychological Rehabilitation 17, 551-566.

- 67.Thöne A M I, E L Glisky. (1995) Learning name-face associations in memory impaired patients: a comparison of different training procedures. , Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society 1, 29-38.

- 68.Mueller-Pfeiffer C, Rufibach K, Perron N, Wyss D, Kuenzler C. (2012) Global functioning and disability in dissociative disorders. , Psychiatry Research 200, 475-481.

- 69.D L McLellan. (1991) Functional recovery and the principles of disability medicine. , In M Swash, J Oxbury(Eds.), Clinical Neurology, ChurchillLivingstone,Edinburgh,UK 768-790.

- 71.G P Prigatano. (1999) Principles of Neuropsychological Rehabilitation.OxfordUniv.Press. , New York, NY, USA

- 72.Diller L, Ben-Yishay Y. (2002) The clinical utility and cost effectiveness of holistic, milieu oriented, rehabilitation programs. In G. Prigatano and N. Pliskin (Eds.), Clinical Neuropsychological and Cost Outcome Research: A Beginning, Psychology Press,NewYork,NY,USA 293-312.

- 73.K D Cicerone. (2012) Facts, theories, values: shaping the course of neurorehabilitation. The 60thJohn Stanley Coulter memorial lecture. , Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 93, 188-191.

- 74.K D Cicerone, D M Langenbahn, Braden C, J F Malec, Kalmar K. (2011) Evidence-based cognitive rehabilitation: updated review of the literature from2003through2008. , Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 92, 519-530.

- 75.K D Cicerone, Mott T, Azulay J, M A Sharlow-Galella, W J Ellmo. (2008) A randomized controlled trial of holistic neuropsychologic rehabilitation after traumatic brain injury. , Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 89, 2239-2249.

- 76.B A Wilson, H C Emslie, Quirk K, J. (2001) Reducing everyday memory and planning problems by means of a paging system: a randomized control crossover study. , Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry 70, 477-482.

- 77.R L Wood, N A Rutherford. (2005) Psychosocial adjustment 17 years after severe brain injury. , Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry 77, 1-4.

- 78.R A Bryant, Das P. (2012) The neural circuitry of conversion disorder and its recovery. , Journal of Abnormal Psychology 121, 289-296.

- 79.Fujiwara E, Brand M, Borsutzky S, Steingass H-P, H J Markowitsch. (2008) Cognitive performance of detoxified alcoholic Korsakoff syndrome patients remains stable over two years. , Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology 30, 576-587.

- 80.Fish J, B A Wilson, Manly T. (2010) The assessment and rehabilitation of prospective memory problems in people with neurological disorders: A review. , Neuropsychological Rehabilitation 20, 161-179.

- 81.Plancher G, Tirard A, Gyselinck V, Nicolas S, Piolino P. (2012) Using virtual reality to characterize episodic memory profiles in amnestic mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease: influence of active and passive encoding. , Neuropsychologia 50, 592-602.

- 82.B A Wilson, Cockburn J, A D Baddeley. (1985) The Rivermead Behavioural Memory Test. Thames Valley Test Comp. , Reading, UK

- 83.M P Chevignard, Taillefer C, Picq C, Poncet F, Noulhiane M. (2008) Ecological assessment of the dysexecutive syndrome using execution of a cooking task. , Neuropsychological Rehabilitation 18, 461-485.

- 84.B A Wilson, H C Emslie, Quirk K, J. (2001) Reducing everyday memory and planning problems by means of a paging system: a randomized control crossover study. , Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry 70, 477-482.

- 85.Grewe P, Khosik A, Flentge D, Dyck E, Botsch M. (2013) Initial evaluation of learning real-life cognitive abilities in a novel 360°-virtual reality supermarket: A feasibility study. doi: 10.1186/1743-0003-10-42. , Journal of Neuroengineering and Rehabilitation 10, 42.

- 86.Hersch N, Treadgold L. (1994) NeuroPage: the rehabilitation of memory dysfunction by prosthetic memory and cueing. , NeuroRehabiliation 4, 187-197.

- 87.Brooks B M, F D Rose. (2003) The use of virtual reality in memory rehabilitation: current findings and future directions. , NeuroRehabilitation 18, 147-157.

- 88.E De Joode, C van Heugten, Verhey F, M van Boxtel. (2010) Efficacy and usability of assistive technology for patients with cognitive deficits: a systematic review. , Clinical Rehabilitation 24, 701-714.

- 89.Lahera G, Benito A, J M Montes, Fernandez-Liria A, C M Olbert. (2013) Social cognition and interaction training (SCIT) for outpatients with bipolar disorder. , Journal of Affective Disorders 146, 132-136.

- 90.Babcock L, B G Kurowski, Zhang N, J W Dexheimer, Dyas J.(2017)Adolescents with mild traumatic brain injury get SMART: An analysis of a novel web-based intervention.Telemedicine. , Journal and E-Health 23, 600-607.

- 91.B G Kurowski, S L Wade, J W Dexheimer, Dyas J, Zhang N.(2016)Feasibility and potential benefits of a web-based intervention delivered acutely after mild traumatic brain injury in adolescents: A pilot study.Journal of Head Trauma and Rehabilitation. 31, 369-378.

- 92.Tsaousides T, Spielman L, Kajankova M, Guetta G, Gordon W.(2017)Improving emotion regulation following web-based group intervention for individuals with traumatic brain injury.Journal of Head Trauma and Rehabilitation. 32, 354-365.

- 93.Pommerenke K, Staniloiu A, H J Markowitsch, Eulitz H, Gütler R. (2012) Ein Fall von retrograder Amnesie nach Resektion eines Medullablastoms – psychogen/funktionell oder organisch?. , Neurologie & Rehabilitation 18, 106-116.

- 94.Linden M, Hawley C, Blackwood B, Evans J, Anderson V.(2016)Technological aids for the rehabilitation of memory and executive functioning in children and adolescents with acquired brain injury. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011020.pub2.Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews7,CD011020.

- 95.K I Toivonen, Zernicke K, L E Carlson.(2017)Web-based mindfulness interventions for people with physical health conditions: Systematic review.doi: 10.2196/jmir.7487. , Journal of Medical Internet Research 19, 303.

- 96.S L Bernecker, Banschback K, G D Santorelli, Constantino M J.(2017)A web-disseminated self-help and peer support program could fill gaps in mental health care: Lessons from a consumer survey.doi: 10.2196/mental.4751. , Journal of Medical Internet Research Mental Health 4, 5.

- 97.Mayo-Wilson E.andMontgomery P(2013)Media-delivered cognitive behavioural therapy and behavioural therapy (self-help) for anxiety disorders in adults.Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews9,CD005330.doi:. 10-1002.

- 98.J V Olthuis, M C Watt, Bailey K, J A Hayden.andStewart SH(2015) Therapist-supported Internet cognitive behavioural therapy for anxiety disorders in adults. doi:. 10.1002/14651858.CD011565.Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews3 011565.

- 99.Stratton E, Lampit A, Choi I, R A Calvo, S B Harvey. (2017) Effectiveness of eHealth interventions for reducing mental health conditions in employees: A systematic review and meta-analysis. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0189904.PLoSOne 12. 0189904.

- 100.UnlüB,Riper H,vanStratenA,CuijpersP(2018) doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-11-101;11. Guided self-help on the Internet for Turkish migrants with depression: the design of a randomized controlled trial.Trials101.

- 101.S P LaCoursiere.(2001)A theory of online social support.Advances in. , Nursing Science 24, 60-77.

- 102.White M, S M Dorman. (2001) Receiving social support online: implications for health education.Health. , Education Research 16, 693-707.

Cited by (29)

This article has been cited by 29 scholarly works according to:

Citing Articles:

Legal and Criminological Psychology (2025) OpenAlex

Springer eBooks (2025) OpenAlex

(2025) Crossref

Memory (2025) OpenAlex

Pamela J Radcliffe, Lawrence Patihis - Memory (2025) Semantic Scholar

Memory (2025) Crossref

Neema J. Kivuyo, K. Otieno - Journal of Research Innovation and Implications in Education (2024) Semantic Scholar

Eastern African Literary and Cultural Studies (2024) Crossref

Eastern African Literary and Cultural Studies (2023) OpenAlex

European journal of psychotraumatology (2023) OpenAlex

Robin P A van der Linde, R. Huntjens, Nathan Bachrach, M. Rijkeboer, A. de Jongh et al. - European Journal of Psychotraumatology (2023) Semantic Scholar

European Journal of Psychotraumatology (2023) Crossref

Keqing Li, William T Yang, Alexander G Perez - Cureus (2021) Semantic Scholar

Case Reports in Psychiatry (2020) OpenAlex

Liyew Agenagnew, Elias Tesfaye, Selamawit Alemayehu, Mathewos Masane, Tilahun Bete et al. - Case Reports in Psychiatry (2020) Semantic Scholar

Case Reports in Psychiatry (2020) Crossref

Neuropsychologia (2020) OpenAlex

A. Staniloiu, A. Kordon, H. Markowitsch - Neuropsychologia (2020) Semantic Scholar

A. Husain - Neurological and Mental Disorders (2019) Semantic Scholar

H. Markowitsch, Angelica Staniloiu - Nerven kitzeln (2019) Semantic Scholar